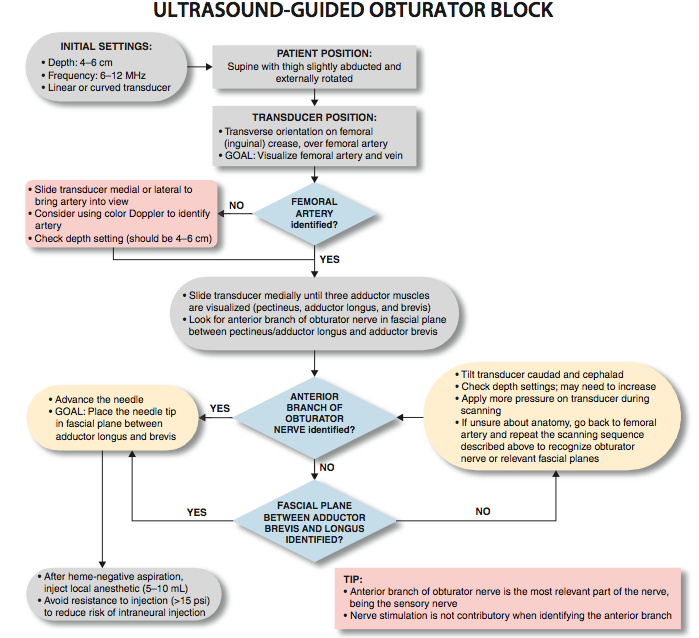

Ultrasound-Guided Obturator Nerve Block

Figure 1: Needle insertion using an in-plane technique to accomplish an obturator nerve block. Essentials

General Considerations There is renewed interest in obturator nerve block because of the recognition that the obturator nerve is spared after a "3-in-1 block" and yet can be easier accomplished using ultrasound guidance. In some patients, the quality of postoperative analgesia is improved after knee surgery when an obturator nerve block is added to a femoral nerve block. However, a routine use of the obturator block does not result in improved analgesia in all patients having knee surgery. For this reason, obturator block is used selectively. Ultrasound-guided obturator nerve block is simpler to perform, more reliable, and associated with patient discomfort when compared with surface landmark-based techniques. There are two approaches to performing ultrasound-guided obturator nerve block. The interfascial injection technique relies on injecting local anesthetic solution into the fascial planes that contain the branches of the obturator nerve. With this technique, it is not important to identify the branches of obturator nerve on the sonogram but rather to identify the adductor muscles and the fascial boundaries within which the nerves lie. This is similar in concept to other fascial plane blocks (e.g. transversus abdominis plane block [TAP]) where local anesthetic solution is injected between the internal oblique and transverse abdominis muscles without the need to indentify the nerves. Alternatively, the branches of the obturator nerve can be visualized with ultrasound imaging and blocked after eliciting a motor response.

Anatomy

Figure 2: Cross-sectional anatomy of relevance to the obturator nerve block. Shown are femoral vessels (FV, FA), pectineus muscle, adductor longus (ALM), adductor brevis (ABM), and adductor magnus (AMM) muscles. The anterior branch of the obturator nerve is seen between ALM and ABM, whereas the posterior branch is seen between ABM and AMM.  Figure 3: Anterior branch (Ant. Br.) of the obturator nerve (ObN) is seen between the adductor longus (ALM) and the adductor brevis (ABM), whereas the posterior branch (Post. Br.) is seen between the ABM and the adductor magnus (AMM). The obturator nerve forms in the lumbar plexus from the anterior primary rami of L2-L4 roots and descends to the pelvis in the psoas muscle. In most individuals, the nerve divides into an anterior branch and posterior branch before exiting the pelvis through the obturator foramen. In the thigh, at the level of the femoral crease, the anterior branch is located between the fascia of pectineus and adductor brevis muscles. The anterior branch lies further caudad between the pectineus and adductor brevis muscles. The anterior branch provides motor fibers to the adductor muscles and cutaneous branches to the medial aspect of the thigh. The anterior branch has a great variability in the extent of sensory innervation of the medial thigh. The posterior branch lies between the fascial planes of the adductor brevis and adductor mag- nus muscles (Figures 2 and 3). The posterior branch is primarily a motor nerve for the adductors of the thigh; however it also may provide articular branches to the medial aspect of the knee joint. The articular branches to the hip joint usually arise from the obturator nerve proximal to its division and only occasionally from the individual branches (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The course and divisions of the obturator nerve and their relationship to the adductor muscles. Distribution of Blockade Because there is great variability in the cutaneous innervation to the medial thigh, demonstrated weakness or absence of adductor muscle strength is the best method of documenting a successful obturator nerve block, rather than a decreased skin sensation in the expected territory. However, the adductor muscles of the thigh may have co-innervation from the femoral nerve (pectineus) and sciatic nerve (adductor magnus). For this reason, complete loss of adductor muscle strength is also uncommon despite a successful obturator nerve block. Equipment Equipment needed includes the following:

Landmarks and Patient Positioning With the patient supine, the thigh is slightly abducted and laterally rotated. The block can be performed either at the level of femoral (inguinal) crease medial to the femoral vein or 1 to 3 cm inferior to the inguinal crease on the medial aspect (adductor compartment) of the thigh (Figure 5).

Technique

Figure 5: A transducer position to image the obturator nerve. The transducer is positioned medial to the femoral artery slightly below the femoral crease. The interfascial approach is performed at the level of the femoral crease. With this technique, it is important to identify the adductor muscles and their fascial planes in which the individual nerves are enveloped. With the patient supine, the leg is slightly abducted and externally rotated. The ultrasound transducer is placed to visualize the femoral vessels. The transducer is advanced medially along the crease to identify the adductor muscles and their fasciae. The anterior branch is sandwiched between the pectineus and adductor brevis muscles, whereas the posterior branch is located the fascial plane between the adductor brevis and adductor magnus muscles. The block needle is advanced to initially position the needle tip between the pectineus and adductor brevis at the junction of middle and posterior third of their fascial interface (Figure 6). At this point, 5 to 10 mL of local anesthetic solution is injected. The needle is advanced further to position the needle tip between the adductor brevis and adductor magnus muscles, and 5 to 10 mL of local anesthetic is injected (Figure 6B). It is important for the local anesthetic solution to spread into the interfascial space and not be injected into the muscles. Correct injection of local anesthetic solution into the interfascial space results in accumulation of the injectate between target muscles. The needle may have to be repositioned to allow for precise interfascial injection. Alternatively, the cross-sectional image of branches of the obturator nerve can be obtained by scanning 1 to 3 cm distal to the inguinal crease on the medial aspect of thigh. The nerves appear as hyperechoic, flat, lip-shaped structures invested in the fascia of adductor muscles. The anterior branch is located between the adductor longus and adductor brevis muscles, whereas the posterior branch is between the adductor brevis and adductor magnus muscles. An insulated block needle attached to the nerve stimulator is advanced toward the nerve either in an out-of-plane or in-plane trajectory. After eliciting the contraction of the adductor muscles, 5 to 7 mL of local anesthetic is injected around each branch of the obturator nerve (Figure 6B).

Figure 6:(A) Needle paths required to reach the anterior branch (1) and the posterior branch (2) of the obturator nerve (ObN). (B) Simulated dispersion of the local anesthetic to block the anterior (1) and posterior (2) branches of the obturator nerve. In both examples, an in-plane needle insertion is used.

|

| 02/20/2016(+ 2016 Dates) | |

| 01/27/2016 | |

| 03/17/2016 | |

| 04/20/2016 | |

| 09/23/2016 | |

| 10/01/2024 |

![[advertisement] gehealthcare](../../../files/banners/banner1_250x600/GEtouch(250X600).gif)

![[advertisement] concertmedical](../../../files/bk-nysora-ad.jpg)

Post your comment