Transgluteal / Anterior Approach

Figure 1-1: (A) Needle insertion for the transgluteal (posterior) approach to sciatic nerve block. (B) Needle insertion for anterior sciatic block. Essentials Transgluteal (Posterior) Approach

Anterior Approach

PART 1: TRANSGLUTEAL APPROACH General Considerations  Figure 1-2:The course and motor innervation of the sciatic nerve. The posterior approach to sciatic nerve block has wide clinical applicability for surgery and pain management of the lower extremity. Consequently, a sciatic block is one of the more commonly used techniques in our practice. In contrast to a common belief, this block is relatively easy to perform and associated with a high success rate. It is particularly well-suited for surgery on the knee, calf, Achilles tendon, ankle, and foot. It provides complete anesthesia of the leg below the knee with the exception of the medial strip of skin, which is innervated by the saphenous nerve. When combined with a femoral nerve or lumbar plexus block, anesthesia of the entire lower extremity can be achieved. Functional Anatomy The sciatic nerve is formed from the L4 through S3 roots. These roots form the sacral plexus on the anterior surface of the lateral sacrum and converge to become the sciatic nerve on the anterior surface of the piriformis muscle. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the body and measures nearly 2 cm in breadth at its origin. The course of the nerve can be estimated by drawing a line on the back of the thigh beginning from the apex of the popliteal fossa to the midpoint of the line joining the ischial tuberosity to the apex of the greater trochanter. The sciatic nerve also gives off numerous articular (hip, knee) and muscular branches. The sciatic nerve exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis and descends between the greater trochanter of the femur and the ischial tuberosity, superficial to the external rotators of the hip (obturator internus, the gemelli muscles, and quadratus femoris) (Figures 1-2 and 1-3). On its medial side, the sciatic nerve is accompanied by the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh and the inferior gluteal artery. The articular branches of the sciatic nerve arise from the upper part of the nerve and supply the hip joint by perforating the posterior part of its capsule. Occasionally, these branches are derived directly from the sacral plexus. The muscular branches of the sciatic nerve are distributed to the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus muscles, and to the ischial head of the adductor magnus. The two components of the nerve (tibial and common peroneal) diverge approximately 4 to 10 cm above the popliteal crease to separately continue their paths into the lower leg.

Figure 1-3: Anatomy of the sciatic nerve at the subgluteal location. (1) sciatic nerve. (2) nerve branch to the gluteus muscle. (3) ischial bone. (4) greater trochanter. (5) posterior superior iliac spine. (6) gluteus muscle. Distribution of Blockade  Figure 1-4: Sensory innervation of sciatic nerve and its terminal branches.  Figure 1-5: The patient is positioned in a lateral oblique position with the dependent leg extended and the leg to be blocked flexed in the knee. A sciatic nerve block results in anesthesia of the skin of the posterior aspect of the thigh, hamstring, and biceps femoris muscles; part of the hip and knee joint; and the entire leg below the knee with the exception of the skin of the medial aspect of the lower leg (Figure 1-4). Depending on the level of surgery, the addition of a saphenous or femoral nerve block may be required to provide coverage for this area. Single Injection Sciatic Nerve Block Equipment A standard regional anesthesia tray is prepared with the following equipment:

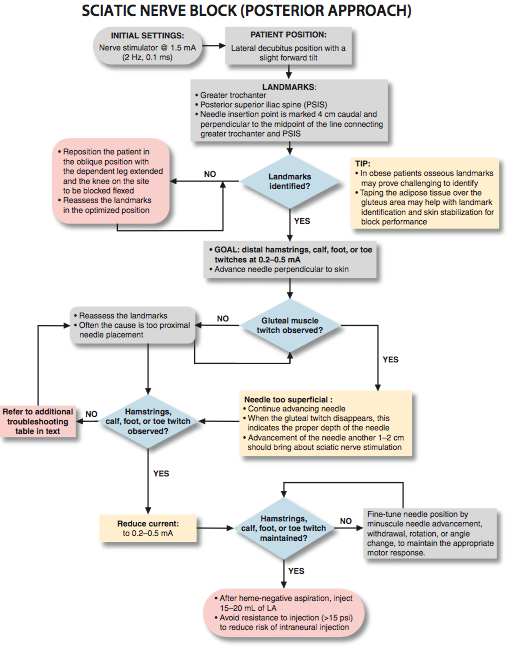

Landmarks and Patient Positioning The patient is in the lateral decubitus position tilted slightly forward (Figure 1-5). The foot on the side to be blocked should be positioned over the dependent leg so that elicited motor response of the foot or toes can be easily observed.

Landmarks for the posterior approach to a sciatic blockade are easily identified in most patients. A proper palpation technique is important to adhere to because the adipose tissue over the gluteal area can obscure these bony prominences. The landmarks are outlined with a marking pen: 1. Greater trochanter (Figure 1-6) 2. Posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) (Figure 1-7) 3. Needle insertion point 4 cm distal to the midpoint between landmarks 1 and 2 (Figure 1-8) A line between the greater trochanter and the PSIS is drawn and divided in half. Another line passing through the midpoint of this line and perpendicular to it is extended 4 cm caudal and marked as the needle insertion point.

Technique After skin disinfection, local anesthetic is infiltrated subcutaneously at the needle insertion site. The operator should assume an ergonomic position to allow precise needle maneuvering and monitoring of the responses to nerve stimulation. The fingers of the palpating hand should be firmly pressed on the gluteus area to decrease the skin to nerve distance. Also, the skin between the index and middle fingers should be stretched to allow greater precision during block placement (Figure 1-9). The palpating hand should not be moved during the entire procedure. Even small movements of the palpating hand can change the position of the needle insertion site because of the highly movable skin and soft tissues in the gluteal region. The needle is introduced perpendicular to the spherical skin plane. Initially, the nerve stimulator should be set to deliver a current intensity of 1.5 mA to allow for the detection of both twitches of the gluteal muscles as the needle passes through tissue layers and stimulation of the sciatic nerve. As the needle is advanced, twitches of the gluteal muscles are observed first. These twitches merely indicate the needle position is still too shallow. Once the gluteal twitches disappear, brisk response of the sciatic nerve ensues (hamstring, calf, foot, or toe twitches). After an initial stimulation of the sciatic nerve is obtained, the stimulating current is gradually decreased until twitches are still seen or felt at 0.2 to 0.5 mA. Typically, this occurs at a depth of 5 to 8 cm. At this low current intensity, any observed motor response is from the stimulation of the sciatic nerve, rather than direct muscle stimulation (false twitch). After negative aspiration for blood, 15 to 20 mL of local anesthetic is injected slowly. Any resistance to the injection of local anesthetic should prompt cessation of the injection and withdrawal of the needle by 1 mm before reattempting to inject. Persistent resistance to injection should prompt complete needle withdrawal and flushing to ensure the patency of the needle before reattempting the procedure.

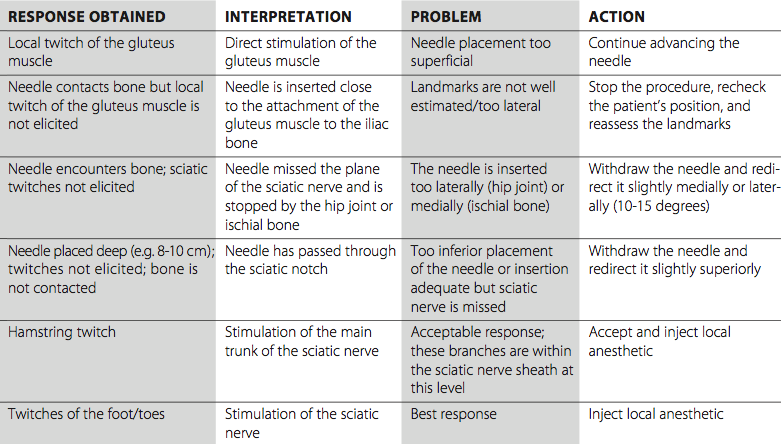

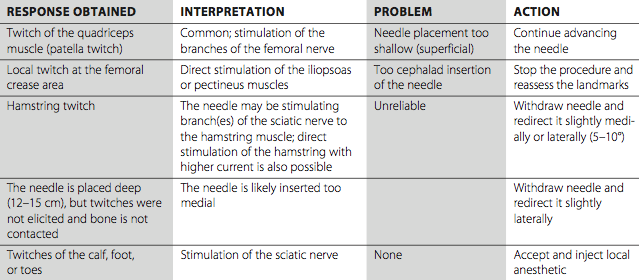

Troubleshooting Table 1-1 lists some common responses to nerve stimulation and the course of action to take to obtain the proper response.

Block Dynamics and Perioperative Management This technique may be associated with patient discomfort because the needle passes through the gluteus muscles. Adequate sedation and analgesia are important to ensure the patient is still and tranquil. Typically, we use midazolam 2 to 4 mg after the patient is positioned and alfentanil 500 to 750 µg just before the needle is inserted. A typical onset time for this block is 10 to 25 minutes, depending on the type, concentration, and volume of local anesthetic used. The first signs of onset of the blockade are usually a report by the patient that the foot "feels different" or an inability to wiggle the toes. Table 1-1 Some Common Responses to Nerve Stimulation and Course of Action for Proper Response

Continuous Lumbar Plexus Block Adequate experience with the single-injection technique is necessary to ensure efficacy and safety of the continuous block. The procedure is quite similar to the single-injection procedure; however, a slight angulation of the needle caudally is necessary after obtaining the nerve response to facilitate threading of the catheter. This technique can be used for surgery and postoperative pain management in patients undergoing a wide variety of lower leg, foot, and ankle surgeries. In our practice, perhaps the single most important indication for use of this block is for amputation of the lower extremity. Equipment A standard regional anesthesia tray is prepared with the fol- lowing equipment:

Kits come in two varieties based on catheter construction: nonstimulating (conventional) and stimulating catheters. During the placement of a nonstimulating catheter, the needle is advanced first until appropriate twitches are obtained. Then 5 to 10 mL of local anesthetic or other injectate (e.g., D5W) is injected to "open up" a space for the catheter to facilitate its insertion. The catheter is threaded through the needle until approximately 3 to 5 cm is protruding beyond the tip of the needle. The needle is withdrawn, the catheter secured, and the remaining local anesthetic is injected via the catheter. Stimulating catheters are insulated and have a filament or core that transmits current to a bare metal tip. After obtaining twitches via the needle, the catheter is advanced with the nerve stimulator guidance while the motor response of the foot, calf, or toes is maintained. With the catheter technique, motor response of ≤1.0 mA is adequate. If the motor response is lost, the catheter can be withdrawn until it reappears, and the catheter is then readvanced while maintaining the response. This method requires that only nonconducting solution be injected through the needle (e.g., dextrose) prior to catheter advancement. Landmarks and Patient Positioning Proper patient positioning at the outset and maintenance of this position during performance of a continuous sciatic nerve blockade is crucial for precise catheter placement. The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position similar to the single-injection block. A slightly forward pelvic tilt prevents "sagging" of the soft tissues in the gluteal area and significantly facilitates block placement. The landmarks for a continuous sciatic block are the same as those in the single-injection technique (Figure 1-8): 1. Greater trochanter 2. Posterior superior iliac spine 3. Needle insertion site 4 cm caudal to the midpoint of the line between landmarks 1 and 2 Technique  Figure 1-10: nsertion of the catheter for continuous sciatic nerve block. The continuous sciatic block technique is similar to the single-injection technique. With the patient in the lateral decubitus position and tilted slightly forward, the landmarks are identified and marked with the pen. After a thorough cleaning of the area with an antiseptic solution, the skin at the needle insertion site is infiltrated with local anesthetic. The palpating hand is positioned and fixed around the site of needle insertion to shorten the skin to nerve distance. A 10-cm continuous block needle is connected to the nerve stimulator and inserted perpendicularly to the skin (Figure 1-10). The initial intensity of the stimulating current should be 1.0 to 1.5 mA. As the needle is advanced, twitches of the gluteus muscle are observed first. Deeper needle advancement results in stimulation of the sciatic nerve. The principles of nerve stimulation and needle redirection are identical to those for the single-injection technique. After obtaining the appropriate twitches, the needle is manipulated until the desired response (twitches of the hamstrings muscles or foot) is seen or felt using a current of 0.5-1.0 mA. The catheter should be advanced 3-5 cm beyond the needle tip. The needle is withdrawn back to the skin level, and the catheter advanced simultaneously to prevent inadvertent removal of the catheter. The catheter is checked for inadvertent intravascular placement and secured to the buttock using an adhesive skin preparation such as benzoin or Dermabond, followed by application of a clear occlusive dressing. The infusion port should be clearly marked "continuous nerve block." Continuous Infusion Continuous infusion is always initiated after administra- tion of an initial bolus of dilute local anesthetic through the needle or catheter. For this purpose, we routinely use 0.2% ropivacaine 15 to 20 mL. Diluted bupivacaine or levobupivacaine are suitable but can result in more pronounced motor blockade. The infusion is maintained at 5 to 10 mL/h when a patient-controlled regional analgesic dose (5 mL every 60 minutes) is planned.

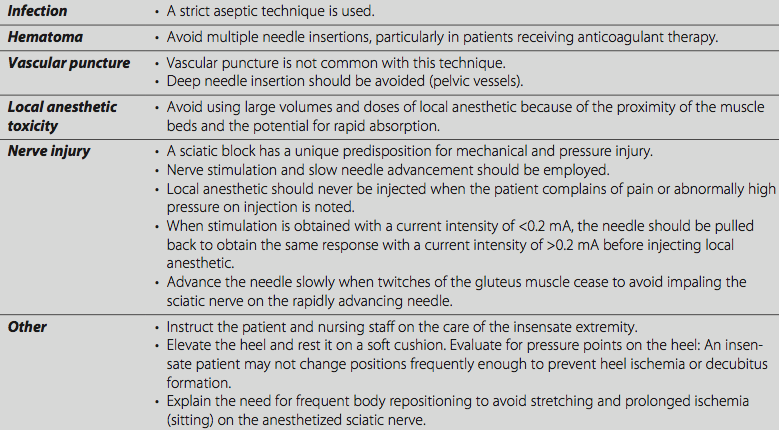

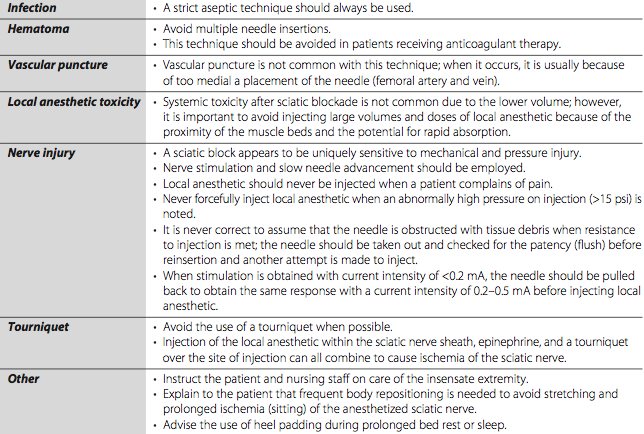

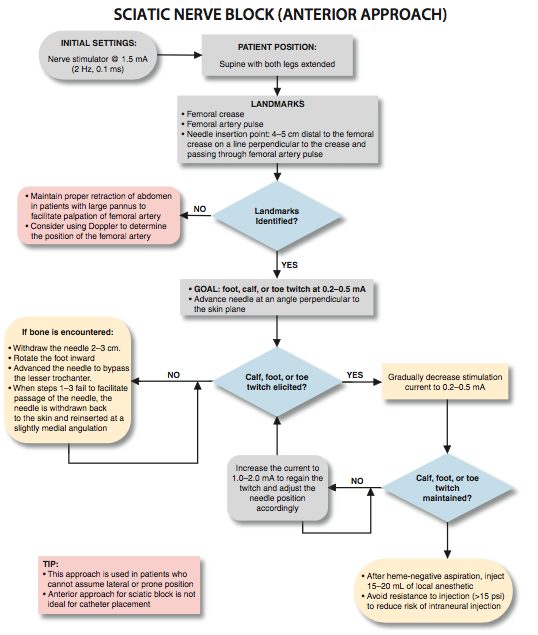

Complications and How to Avoid Them Table 1-2 lists some general and specific instructions on possible complications and methods used to avoid them. Table 1-2: Complications of Sciatic Nerve Block and Preventive Techniques     PART 2: ANTERIOR APPROACH General Considerations The anterior approach to sciatic block is an advanced nerve block technique. The block is well-suited for surgery on the leg below the knee, particularly on the ankle and foot. It provides complete anesthesia of the leg below the knee with the exception of the medial strip of skin, which is innervated by the saphenous nerve. When combined with a femoral nerve block, this procedure results in anesthesia of the entire knee and leg. It should be noted that the anterior approach may have less utility compared with the posterior approach. The sciatic nerve is blocked more distally, and a higher level of skill is required to achieve reliable anesthesia. Consequently, we reserve the use of this block for patients who cannot be repositioned into the lateral position needed for the posterior approach. This technique is not ideal for catheter insertion because of the deep location and perpendicular angle of insertion required to reach the sciatic nerve. Functional Anatomy The sciatic nerve is formed from the L4 through S3 roots. The roots of the sacral plexus combine on the anterior surface of the sacrum and are assembled into the sciatic nerve on the anterior surface of the piriformis muscle. The course of the nerve can be estimated by drawing a line on the back of the thigh from the apex of the popliteal fossa to the midpoint of a line joining the ischial tuberosity to the apex of the greater trochanter. The nerve exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic notch and gives off numerous articular (hip, knee) and muscular branches. Once in the upper thigh, it continues its descent behind the lesser trochanter and becomes completely covered by the femur. The only part of the nerve accessible to blockade through an anterior approach is a short segment slightly above and below the lesser trochanter. The muscular branches of the sciatic nerve are distributed to the biceps femoris, semiten- dinosus, and semimembranosus, and to the ischial head of the adductor magnus.

Distribution of Blockade A sciatic nerve block through the anterior approach results in anesthesia of the hamstring muscles below the blockade and the entire leg below the knee (including the ankle and foot) except for a strip of skin over the medial aspect. The distal two thirds of the hamstring muscles are also anesthetized. Neither the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh and articular branches of the hip are anesthetized, nor the skin over the medial aspect of the leg below, because it is innervated by the saphenous nerve, a branch of the femoral nerve. Consequently, the anterior approach to sciatic block should be chosen for selected patients undergoing knee or below-knee surgery who also are unable to be positioned for the posterior approach. A proximal thigh tourniquet should be reconsidered with this technique because of the risk of prolonged ischemia of the sciatic nerve, particularly when epinephrine-containing solutions of local anesthetics are used. Single Injection Infraclavicular Block Equipment A standard regional anesthesia tray is prepared with the following equipment:

Landmarks and Patient Positioning The patient is in the supine position with both legs fully extended.

The following landmarks should be outlined routinely using a marking pen: 1. Femoral crease (Figure 2-1) 2. Femoral artery pulse (Figure 2-2) 3. Needle insertion point is marked 4 to 5 cm distally to the femoral crease on a line passing through the pulse of the femoral artery and perpendicularly to the femoral crease (Figures 2-3 and 2-4). A line between the greater trochanter and the PSIS is drawn and divided in half. Another line passing through the midpoint of this line and perpendicular to it is extended 4 cm caudal and marked as the needle insertion point.

Figure 2-5: Needle insertion for anterior sciatic block. Technique After cleaning the area with an antiseptic solution, local anes- thetic is infiltrated subcutaneously at the determined needle insertion site. The operator should stand on the side of the patient to be blocked and have the ipsilateral foot in the line of vision to be able to monitor the patient and the responses to nerve stimulation. The fingers of the palpating hand should be firmly pressed against the quadriceps muscle to decrease the skin-nerve distance and stabilize the needle path. The needle is introduced at an angle perpendicular to the skin plane (Figure 2-5). Initially, the nerve stimulator should be set to deliver a 1.5-mA current, as with all "deep" blocks. The current of higher intensity results in an exaggerated motor response, decreasing the chance of missing this twitch of the foot or toes during nerve localization. The twitch of the foot or toes typically occurs at a depth of 10 to 12 cm. After obtaining negative results from an aspiration test for blood, 15 to 20 mL of local anesthetic is slowly injected. Any resistance to the injection of local anesthetic should prompt cessation of the injection attempt, followed by slight withdrawal. Persistent resistance to injection should prompt complete needle withdrawal and flushing of the needle before reattempting the block; see "tips" for more explanation of the importance of this strategy.

Figure 2-6: Needle pass required to reach the sciatic nerve through the anterior approach. Note that the lesser trochanter of the femur partially obscures the sciatic nerve. (1) Internal rotation of the leg (arrow) is beneficial in allowing access of the needle to the sciatic nerve (2). Troubleshooting Some common responses to nerve stimulation and the course of action to take to obtain the proper response are given in Table 2-1. Table 2-1: Common Responses to Nerve Stimulation and Course of Action for Proper Response

Figure 2-7: When the needle fails to pass by the trochanter minor despite internal leg rotation, the needle is inserted 1-2 cm medial to the initial insertion and advanced in a slight medial to lateral direction to reach the sciatic nerve. Block Dynamics and Perioperative Management Performance of the anterior approach to a sciatic block is associated with patient discomfort because the needle must transverse multiple muscle planes on its way to the sciatic nerve. The administration of midazolam 2 to 4 mg after the patient is positioned and alfentanil 500-1000 mg just before infiltration of local anesthetic is beneficial to allay anxiety and decrease discomfort during the procedure in most patients. A typical onset time for this block is 20 to 30 minutes, depending on the type, concentration, and volume of local anesthetic used. The first sign of blockade onset is usually a report by the patient that the foot "feels different" or an inability to wiggle the toes.

Complications and How to Avoid Them Table 2-2 lists some general and specific instructions on possible complications and methods that can be used to avoid them. Table 2-2: Complications of Anterior Approach to Sciatic Nerve Block and Preventive Techniques    |

| 02/20/2016(+ 2016 Dates) | |

| 01/27/2016 | |

| 03/17/2016 | |

| 04/20/2016 | |

| 09/23/2016 | |

| 10/01/2024 |

![[advertisement] B Braun](files/banners/banner1_250x600/Contiplex-C-NYSORA.jpg)

![[advertisement] concertmedical](../../../files/bk-nysora-ad.jpg)

A

A

Post your comment