Cervical Plexus Block

|

Figure 1: Needle insertion for superficial cervical plexus block. The needle is inserted behind the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Essentials

General Considerations Cervical plexus block can be performed using two different methods. One is a deep cervical plexus block, which is essentially a paravertebral block of the C2-4 spinal nerves (roots) as they emerge from the foramina of their respective vertebrae. The other method is a superficial cervical plexus block, which is a subcutaneous blockade of the distinct nerves of the anterolateral neck. The most common clinical uses for this block are carotid endarterectomy and excision of cervical lymph nodes. The cervical plexus is anesthetized also when a large volume of local anesthetic is used for an interscalene brachial plexus block. This is because local anesthetic invariably escapes the interscalane groove and layers out underneath the deep cervical fascia where the branches of the cervical plexus are located. The sensory distribution for the deep and superficial blocks is similar for neck surgery, so there is a trend toward favoring the superficial approach. This is because of the potentially greater risk for complications associated with the deep block, such as vertebral artery puncture, systemic toxicity, nerve root injury, and neuraxial spread of local anesthetic. Functional Anatomy

Figure 2: The superficial cervical plexus and its terminal nerves. Anatomy of the superficial cervical plexus and its branches are shown emerging behind the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

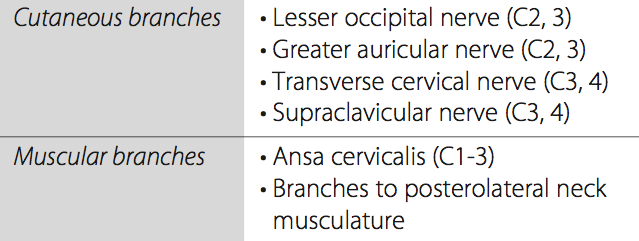

Figure 3: Anatomy of the superficial cervical plexus. (1) Sternocleidomastoid muscle (2) mastoid process (3) clavicle (4) external jugular vein. The cervical plexus is formed by the anterior rami of the four upper cervical nerves. The plexus lies just lateral to the tips of the transverse processes in the plane just behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle, giving off both cutaneous and muscular branches. There are four cutaneous branches, all of which are innervated by roots C2-4. These emerge from the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at approximately its midpoint, and they supply the skin of the anterolateral neck (Figures 2 and 3). The second, third, and fourth cervical nerves typically send a branch each to the spinal accessory nerve or directly into the deep surface of the trapezius to supply sensory fibers to this muscle. In addition, the fourth cervical nerve may send a branch downward to join the fifth cervical nerve and participates in formation of the brachial plexus. The motor component of the cervical plexus consists of the looped ansa cervicalis (C1-C3), from which the nerves to the anterior neck muscles originate, and various branches from individual roots to posterolateral neck musculature (Figure 4). The C1 spinal nerve (the suboccipital nerve) is strictly a motor nerve, and is not blocked with either tech- nique. One other significant muscle innervated by roots of the cervical plexus includes the diaphragm (phrenic nerve, C3,4,5) (Table 1). Table 1: Cervical Plexus Branches  Distribution of Blockade Cutaneous innervation of both the deep and the superficial cervical plexus blocks includes the skin of the anterolateral neck and the ante- and retroauricular areas (Figure 5). In addition, the deep cervical block anesthetizes three of the four strap muscles of the neck, geniohyoid, the prevertebral muscles, sternocleidomastoid, levator scapulae, the scalenes, trapezius, and the diaphragm (via blockade of the phrenic nerve).

Figure 4: The roots origin of the cervical plexus.

Figure 5: Sensory innervation of the lateral aspect of the head and neck and contribution of the superficial cervical plexus. Superficial Cervical Plexus Block Equipment

Figure 6: Surface landmarks for superficial cervical plexus block. White dot: insertion of the clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Blue dot: Mastoid process. Uncolored circle: Transverse process of C6 vertebrate. Red dot: Needle insertion site at the midpoint between C6 and mastoid process behind the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. A standard regional anesthesia tray is prepared with the following equipment:

Landmarks and Patient Positioning The patient is in a supine or semi-sitting position with the head facing away from the side to be blocked. These are the primary landmarks (Figure 6) for performing this block: 1. Mastoid process 2. Clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid 3. The midpoint of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid (this is aided by identifying the first two landmarks) Maneuvers to Facilitate Landmark Identification The sternocleidomastoid muscle can be better differentiated from the deeper neck structures by asking the patient to raise their head off the table.

Figure 7: Injection of local anesthetic for superficial cervical plexus. The injection is made fan-wise behind the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at a depth of approximately 1 cm in average-size patients. Technique After cleaning the skin with an antiseptic solution, the needle is inserted along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid, and three injections of 5 mL of local anesthetic are injected behind the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle subcutaneously, perpendicularly, cephalad, and caudad in a 'fan' fashion (Figure 7). |

Block Dynamics and Perioperative Management

A superficial cervical plexus block is associated with minor patient discomfort. Small doses of midazolam 1 to 2 mg for sedation and alfentanil 250 to 500 µg for analgesia just before needle insertion should result in a comfortable, cooperative patient during block injection. The onset time for this block is 10 to 15 minutes. Excessive sedation should be avoided before and during head and neck procedures because airway management, when necessary, can prove difficult because access to the head and neck is shared with the surgeon. Due to the complex arrangement of the sensory innervation of the neck and the cross-coverage from the contralateral side, the anesthesia achieved with a cervical plexus block is rarely complete. Although this should not discourage the use of the cervical block, the surgeon must be willing to supplement the block with a local anesthetic if necessary.

|

|

|

Figure 8: Palpation technique to determine location of the transverse process of C6. The head is rotated away from the palpated side while the palpated fingers explore for the most lateral bony prominence, often in the vicinity of the external jugular vein. |

Figure 9: Palpation technique to determine the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. With the head of the patient rotated away from the palpation side, the patient is asked to lift his or her head off of the bed to accentuate the sternocleidomastoid muscle. |

|

|

|

Figure 10: The landmarks for the deep cervical plexus block. White circle indicates the transverse process of C6 The pen is outlining the transverse process of C4. |

Figure 11: Needle insertion for the deep cervical plexus block. The needle is inserted between fingers palpat- ing individual transverse processes. |

|

NYSORA Highlights

|

Deep Cervical Plexus Block

Equipment

A standard regional anesthesia tray is prepared with the following equipment:

![]() Sterile towels and gauze packs

Sterile towels and gauze packs

![]() A 20-mL syringe with local anesthetic, attached via tubing to ½ to 2 in, 22-gauge short bevel needle

A 20-mL syringe with local anesthetic, attached via tubing to ½ to 2 in, 22-gauge short bevel needle

![]() A 3-mL syringe plus 25-gauge needle with local anesthetic for skin infiltration

A 3-mL syringe plus 25-gauge needle with local anesthetic for skin infiltration

![]() Sterile gloves, marking pen, ruler

Sterile gloves, marking pen, ruler

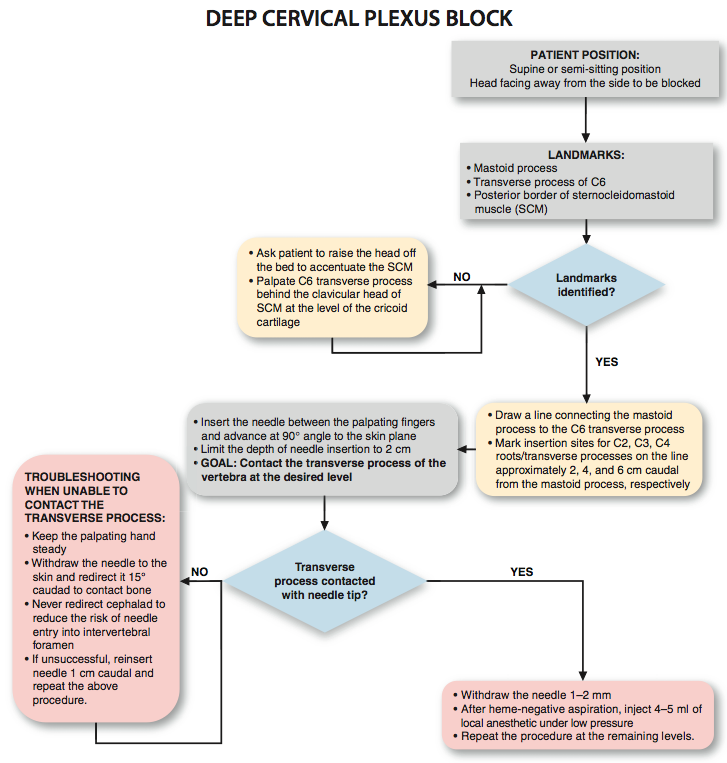

Landmarks and Patient Positioning

The patient is in the same position as for the superficial cervical plexus block. The three landmarks for a deep cervical plexus block are similar to those for the superficial cervical plexus block:

1. Mastoid process

2. Chassaignac tubercle (transverse process of C6)(Figure 8)

3. Posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Figure 9)

To estimate the line of needle insertion overlying the transverse processes, the mastoid process and the transverse process of C6 are identified and marked. The latter is easily palpated behind the clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle just below the level of the cricoid cartilage. Next, a line is drawn connecting the mastoid process to the C6 transverse process. The palpating hand is best positioned just behind the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Once this line is drawn, the insertion sites over C2 through C4 are labeled as follows: C2: 2 cm caudad to the mastoid process, C3: 4 cm caudad to the mastoid process, and C4: 6 cm caudad to the mastoid process (Figure 10).

Maneuvers to Facilitate Landmark Identification

The sternocleidomastoid muscle can be accentuated by asking the patient to raise his or her head off of the table.

Technique

After cleaning the skin with an antiseptic solution, local anesthetic is infiltrated subcutaneously along the line estimating the position of the transverse processes. The local anesthetic is infiltrated over the entire length of the line, rather than at the projected insertion sites. This allows reinsertion of the needle slightly caudally or cranially when the transverse process is not contacted, without the need to infiltrate the skin at a new insertion site. A needle is connected via flexible tubing to a syringe containing local anesthetic. The needle is inserted between the palpating fingers and advanced at an angle perpendicular to the skin plane (Figure 11). The needle should never be oriented cephalad. A slightly caudal orientation of the needle is important to prevent inadvertent insertion of the needle toward the cervical spinal cord. The needle is advanced slowly until the transverse process is contacted. At this point, the needle is withdrawn 1 to 2 mm and firmly stabilized, and 4 to 5 mL of local anesthetic is injected after a negative aspiration test for blood. The needle is removed, and the entire procedure is repeated at consecutive levels.

|

GOAL

|

Troubleshooting Deep Cervical Plexus Blocks

When insertion of the needle does not result in contact with the transverse process within 2 cm, the following maneuvers are used:

1. While avoiding skin movement, keep the palpating hand in the same position and the skin between the fingers stretched.

2. Withdraw the needle to the skin, redirect it 15° inferiorly, and repeat the procedure.

3. Withdraw the needle to the skin, reinsert it 1 cm caudal, and repeat the procedure.

|

NYSORA Highlights

|

Block Dynamics and Perioperative Management

Premedication is useful for patient comfort; however, excessive sedation should be avoided. During neck surgery, airway management can be difficult because the anesthesiologist must share access to the head and neck with the surgeon. Surgeries like carotid endarterectomy require the patient to be fully conscious, oriented, and cooperative during the entire procedure. In addition, excessive sedation and the consequent lack of patient cooperation can result in restlessness and create difficulty for the surgeon. The onset time for this block is 10 to 20 minutes. The first sign is decreased sensation in the area of distribution of the respective components of the cervical plexus. Complications of cervical plexus blocks and strategies to avoid them are listed in Table 2.

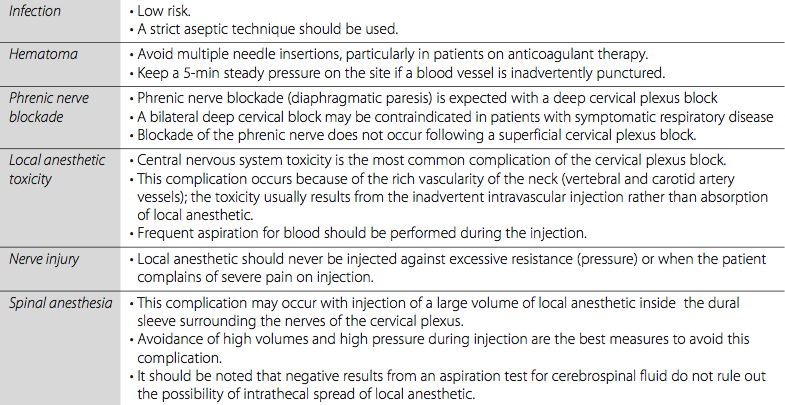

Table 2: Complications and How to Avoid Them

| 12/19/2015(+ 2016 Dates) | |

| 01/27/2016 | |

| 03/17/2016 | |

| 04/20/2016 | |

| 09/24/2016 | |

| 10/01/2024 |

![[advertisement] gehealthcare](../../../files/banners/banner1_250x600/GEtouch(250X600).gif)

![[advertisement] concertmedical](../../../files/bk-nysora-ad.jpg)

Post your comment