Oral and Maxillofacial Regional Anesthesia

Authors: Benaifer D. Dubash, DMD; Adam T. Hershkin, DMD; Paul J. Seider, DMD; Gregory M. Casey, DMD

Affiliation: St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

|

Oral surgical and dental procedures are routinely performed in an outpatient setting. Regional anesthesia is the most common method to anesthetize the patient prior to office based procedures. Many techniques can be employed to achieve anesthesia of the dentition and surrounding hard and soft tissues of the maxilla and mandible. The type of procedure to be performed as well as the location of the procedure will determine the technique of anesthesia to be used. Orofacial anesthetic techniques can be classified into three main categories: local infiltration, field block, and nerve block. The local infiltration technique anesthetizes the terminal nerve endings of the dental plexus. It is indicated when an individual tooth or a specific, isolated area requires anesthesia. The procedure is performed in the direct vicinity of the site of infiltration. The field block anesthetizes the terminal nerve branches in the area of treatment. Treatment can then be performed in an area slightly distal to the site of injection. The deposition of local anesthetic at the apex of a tooth for the purposes of achieving pulpal and soft tissue anesthesia is often employed by many dental and maxillofacial professionals. While this is commonly termed "local infiltration," it is important to note this is a misnomer. Terminal nerve branches are anesthetized in this technique and it is therefore correctly termed a field block. A nerve block anesthetizes the main branch of a specific nerve allowing treatment to be performed in the region innervated by the nerve.1 This chapter will review the essential anatomy of orofacial nerves and detail the practical approach to performing nerve blocks and infiltrational anesthesia for a wide variety of surgical procedures in this region. Anatomy of the Trigeminal Nerve Preparation for Awake Intubation Anesthesia of the teeth and soft and hard tissues of the oral cavity cannot be achieved without knowledge of the trigeminal nerve (fifth cranial nerve) and its branches. Regional, field, and local anesthesia of the maxilla and mandible depend upon the deposition of anesthetic solution near terminal nerve branches or a main nerve trunk of the trigeminal nerve.

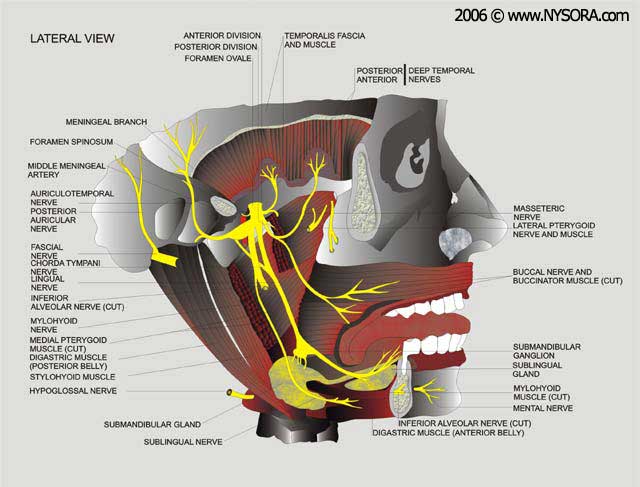

Figure 1: Anatomy of the trigeminal nerve The sensory root of the trigeminal nerve gives rise to the ophthalmic division (V1), maxillary division (V2), and the mandibular division (V3) from the trigeminal ganglion The largest of all the cranial nerves, the trigeminal nerve gives rise to a small motor root originating in the motor nucleus within the pons and medulla oblongata, and a larger sensory root which finds its origin in the anterior aspect of the pons. The nerve travels forward, from the posterior cranial fossa to the petrous portion of the temporal bone, within the middle cranial fossa. Here, the sensory root forms the trigeminal (semilunar or gasserian) ganglion situated within Meckel's cavity on the anterior surface of the petrous portion of the temporal bone. The ganglia are paired; one innervating each side of the face. The sensory root of the trigeminal nerve gives rise to the ophthalmic division (V1), maxillary division (V2), and the mandibular division (V3) from the trigeminal ganglion (Figure 1). The motor root travels from the brainstem along with but separate from the sensory root. It then leaves the middle cranial fossa through the foramen ovale after passing underneath the trigeminal ganglion in a lateral and inferior direction. The motor root exits the middle cranial fossa along with the third division of the sensory root; the mandibular nerve. It then unties with the mandibular nerve to form a single nerve trunk after exiting the skull. The motor fibers supply the muscles of mastication, (masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid, and lateral pterygoid), mylohyoid, anterior belly of the digastric, tensor veli palatini and tensor tympani muscles. Ophthalmic Division (V1) The smallest of the three divisions, the ophthalmic is purely sensory and travels anteriorly in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus in the middle cranial fossa, to the medial part of the superior orbital fissure. Prior to its entrance into the orbit through the superior orbital fissure, the ophthalmic nerve divides into three branches; frontal, nasociliary and lacrimal. The frontal nerve is the largest branch of the ophthalmic division and travels anteriorly in the orbit terminating as the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves. The supratrochlear nerve lies medial to the supraorbital nerve and supplies the skin and conjunctiva of the medial portion of the upper eyelid and the skin over the lower forehead close to the midline. The supraorbital nerve supplies the skin and conjunctiva of the central portion of the upper eyelid, the skin of the forehead, and the scalp as far back as the parietal bone and lambdoid suture. The nasociliary branch travels along the medial aspect of the orbital roof giving off various branches. The nasal cavity and the skin at the apex and ala of the nose are innervated by the anterior ethmoid and external nasal nerves. The mucous membrane of the anterior portion of the nasal septum and lateral wall of the nasal cavity are innervated by the internal nasal nerve. The skin of the lacrimal sac, lacrimal caruncle, and adjoining portion of the side of the nose are innervated by the infratrochlear branch. The ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses are supplied by the posterior ethmoidal nerve. The eyeball is innervated by the short and long ciliary nerves. The lacrimal nerve supplies the skin and conjunctiva of the lateral portion of the upper eyelid and is the smallest branch of the ophthalmic division. Maxillary Division (V2) The maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve is also purely a sensory division. Arising from the trigeminal ganglion in the middle cranial fossa, the maxillary nerve travels forward along the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. Shortly after stemming from the trigeminal ganglion, the maxillary nerve gives off the only branch within the cranium; the middle meningeal nerve. It then leaves the cranium through the foramen rotundum, located in the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. After exiting the foramen rotundum, the nerve enters a space located behind and below the orbital cavity known as the pterygopalatine fossa. After giving off several branches within the fossa the nerve enters the orbit through the inferior orbital fissure at which point it becomes the infraorbital nerve. Coursing along the floor of the orbit in the infraorbital groove the nerve enters the infraorbital canal and emerges onto the face through the infraorbital foramen. The middle meningeal nerve, as previously stated, is the only branch of the maxillary division within the cranium and provides sensory innervation to the dura mater in the middle cranial fossa. Within the pterygopalatine fossa, several branches are given off including the pterygopalatine, zygomatic, and posterior superior alveolar nerves. The pterygopalatine nerves are two short nerves that merge within the pterygopalatine ganglion and then give rise to several branches. They contain postganglionic parasympathetic fibers which pass along the zygomatic nerve to the lacrimal nerve innervating the lacrimal gland, as well as sensory fibers to the orbit, nose, palate, and pharynx. The sensory fibers to the orbit innervate the orbital periosteum. The posterior aspect of the nasal septum, mucous membrane of the superior and middle conchae and the posterior ethmoid sinus are innervated by the nasal branches. The anterior nasal septum, floor of the nose and premaxilla from canine to canine is innervated by a branch known as the nasopalatine nerve. The nasopalatine nerve courses downward and forward from the roof of the nasal cavity to the floor to enter the incisive canal. It then enters the oral cavity through the incisive foramen to supply the palatal mucosa of the premaxilla. The hard and soft palate is innervated by the palatine branches; the greater (anterior) and lesser (middle and posterior) palatine nerves. After descending through the pterygopalatine canal, the greater palatine nerve exits the greater palatine foramen onto the hard palate. The nerve provides sensory innervation to the palatal mucosa and bone of the hard and soft palate. The lesser palatine nerves emerge from the lesser palatine foramen to innervate the soft palate and tonsillar region. The pharyngeal branch leaves the pterygopalatine ganglion from its posterior aspect to innervate the nasopharynx. The zygomatic nerve gives rise to two branches after passing anteriorly from the pterygopalatine fossa to the orbit. The nerve passes through the inferior orbital fissure and divides into the zygomaticofacial and zygomaticotemporal nerves supplying the skin over the malar prominence and skin over the side of the forehead respectively. The zygomatic nerve also communicates with the ophthalmic division via the lacrimal nerve sending fibers to the lacrimal gland. The posterior superior alveolar (PSA) nerve branches off within the pterygopalatine fossa prior to the maxillary nerve's entrance into the orbit. The PSA travels downward along the posterior aspect of the maxilla to supply the maxillary molar dentition including the periodontal ligament and pulpal tissues, as well as the adjacent gingiva and alveolar process. The mucous membrane of the maxillary sinus is also innervated by the PSA. It is of clinical significance to note that the PSA does not always innervate the mesiobuccal root of the 1st molar.1,2 Several dissection studies have been performed tracing the innervation of the 1st molar back to the parent trunk. These studies have demonstrated the variations in innervation patterns of the 1st molar which is of clinical significance when anesthesia of this tooth is desired. In a study by Loetscher and Walton3, twenty nine human maxillae were dissected in order to observe innervation patterns of the 1st molar. The study evaluated the innervation patterns by the posterior, middle, and anterior superior alveolar nerves on the 1st molar. The posterior and anterior superior alveolar nerves were found to be present in 100% (29/29) of specimens. The middle superior alveolar nerve was found to be present 72% of the time (21/29 specimens). Nerves were traced from the 1st molar to the parent branches in eighteen of the specimens. The posterior superior alveolar nerve was found to provide innervation in 72% (13/18) of specimens. The middle superior alveolar nerve provided innervation in 28% (5/18) specimens whereas the anterior superior alveolar nerve did not provide innervation to the 1st molar in any of the specimens. In the absence of the middle superior alveolar nerve, the posterior superior alveolar nerve may provide innervation to the premolar region. In a study by McDaniel4, fifty maxillae were decalcified and dissected in order to demonstrate the innervation patterns of maxillary teeth. The PSA was found to innervate the premolar region in 26% of dissections where the MSA was not present.

Within the infraorbital canal, the maxillary division is known as the infraorbital nerve and gives off the middle and anterior superior alveolar nerves. When present, the middle superior alveolar (MSA) nerve descends along the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus to innervate the 1st and 2nd premolar teeth. It provides sensation to the periodontal ligament, pulpal tissues, gingiva and alveolar process of the premolar region as well as the mesiobuccal root of the 1st molar in some cases.1,2 In a study by Heasman,5 dissections of nineteen human cadaver heads were performed and the MSA was found to be present in seven of the specimens. Loetscher and Walton3 found that the mesial or distal position at which the MSA nerve joins the dental plexus (an anastomosis of the posterior, middle, and anterior superior alveolar nerves described below), determines its contribution to the innervation of the 1st molar. Specimens in which the MSA joined the plexus mesial to the 1st molar were found to have innervation of the 1st molar by the PSA and the premolars by the MSA. Specimens in which the MSA joined the plexus distal to the 1st molar demonstrated innervation of the 1st molar by the MSA. In its absence, the premolar region derives it's innervation from the PSA and ASA nerves.4 The anterior superior alveolar (ASA) nerve descends within the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus. A small terminal branch of the ASA communicates with the MSA to supply a small area of the lateral wall and floor of the nose. It also provides sensory innervation to the periodontal ligament, pulpal tissue, gingiva and alveolar process of the central and lateral incisor and canine teeth. In the absence of the MSA, the ASA has been shown to provide innervation to the premolar teeth. In the previously mentioned study by McDaniel, the ASA was shown to provide innervation to the premolar region in 36% of specimens in which no MSA nerve was found.4 The three superior alveolar nerves anastomose to form a network known as the dental plexus which is comprised of terminal branches coming off the larger nerve trunks. These terminal branches are known as the dental, interdental, and interradicular nerves. The dental nerves innervate each root of each individual tooth in the maxilla by entering the root through the apical foramen and supplying sensation to the pulp. Interdental and interradicular branches provide sensation to the periodontal ligaments, interdental papillae and buccal gingiva of adjacent teeth. The infraorbital nerve divides into three terminal branches after emerging through the infraorbital foramen onto the face. The inferior palpebral, external nasal, and superior labial nerves supply sensory innervation to the skin of the lower eyelid, lateral aspect of the nose, and skin and mucous membranes of the upper lip respectively. Mandibular Division (V3) The largest branch of the trigeminal nerve, the mandibular branch is both sensory and motor, Figure 2. The sensory root arises from the trigeminal ganglion whereas the motor root arises from the motor nucleus of the pons and medulla oblongata. The sensory root passes through the foramen ovale almost immediately after coming off the trigeminal ganglion. The motor root passes underneath the ganglion and through the foramen ovale to unite with the sensory root just outside the cranium forming the main trunk of the mandibular nerve. The nerve then divides into anterior and posterior divisions. The mandibular nerve gives off branches from its main trunk as well as the anterior and posterior divisions.

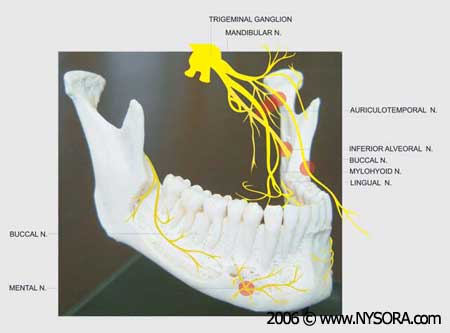

Figure 2: Anatomy of the Mandibular Nerve The main trunk gives off two branches known as the nervus spinosus (meningeal branch) and the nerve to the medial pterygoid. After branching off the main trunk, the nervus spinosus reenters the cranium along with the middle meningeal artery through the foramen spinosum. The nervus spinosus supplies the meninges of the middle cranial fossa as well as the mastoid air cells. The nerve to the medial pterygoid is a small motor branch that supplies the medial (internal) pterygoid muscle. It gives off two braches that supply the tensor tympani and tensor veli palatini muscles. Three motor and one sensory branch are given off by the anterior division of the mandibular nerve. The masseteric, deep temporal, and lateral pterygoid nerves supply the masseter, temporalis and lateral (external) pterygoid muscles respectively. The sensory division known as the buccal (buccinator or long buccal) nerve, runs forward between the two heads of the lateral pterygoid muscle, along the inferior aspect of the temporalis muscle, to the anterior border of the masseter muscle. Here it passes anterolaterally to enter the buccinator muscle however it does not innervate this muscle. The buccinator muscle is innervated by the buccal branch of the facial nerve. The buccal nerve provides sensory innervation to the skin of the cheek, buccal mucosa and buccal gingiva in the mandibular molar region. Branches of the Mandibular Division

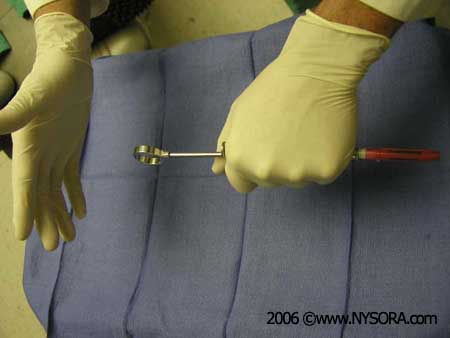

The posterior division of the mandibular branch gives off two sensory branches (the auriculotemporal and lingual nerves) and one branch made up of both sensory and motor fibers (the inferior alveolar nerve). The auriculotemporal nerve crosses the superior portion of the parotid gland, ascending behind the temporomandibular joint and giving off several sensory branches to the skin of the auricle, external auditory meatus, tympanic membrane, temporal region, temporomandibular joint and parotid gland via postganglionic parasympathetic secretomotor fibers from the otic ganglion. The lingual nerve travels inferiorly in the pterygomandibular space between the medial aspect of the ramus of the mandible and the lateral aspect of the medial pterygoid muscle. It then travels anteromedially below the inferior border of the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle deep to the pterygomandibular raphae. The lingual nerve then continues anteriorly in the submandibular region along the hyoglossus muscle, crossing the submandibular duct inferiorly and medially to terminate deep to the sublingual gland. The lingual nerve provides sensory innervation to the anterior two thirds of the tongue, mucosa of the floor of the mouth, and lingual gingiva. The inferior alveolar branch of the mandibular nerve descends in the region between the lateral aspect of the sphenomandibular ligament and the medial aspect of the ramus of the mandible. It travels along with, but lateral and posterior to, the lingual nerve. While the lingual nerve continues to descend within the pterygomandibular space, the inferior alveolar nerve enters the mandibular canal through the mandibular foramen. Just before entering the mandibular canal the inferior alveolar nerve gives off a motor branch known as the mylohyoid nerve which is discussed below. The nerve travels along with the inferior alveolar artery and vein within the mandibular canal and divides into the mental and incisive nerve branches at the mental foramen. The inferior alveolar nerve provides sensation to the mandibular posterior teeth. The incisive nerve is a branch of the inferior alveolar nerve which continues within the mandibular canal to provide sensory innervation to the mandibular anterior teeth. The mental nerve emerges from the mental foramen to provide sensory innervation to the mucosa in the premolar/canine region as well as the skin of the chin and lower lip. The mylohyoid nerve, as previously stated, branches off the inferior alveolar nerve prior to its entry into the mandibular canal. It travels within the mylohyoid groove and along the medial aspect of the body of the mandible to supply the mylohyoid muscle as well as the anterior belly of the digastric.1,2 Maxillary and Mandibular Regional Anesthesia Equipment Administration of regional anesthesia of the maxilla and mandible is achieved via the use of a dental syringe, needle, and anesthetic cartridge. Several types of dental syringes are available for use, however the most common is the breech-loading, metallic, cartridge-type, aspirating syringe. The syringe is comprised of a thumb ring, finger grip, barrel containing the piston with a harpoon, and a needle adaptor (Fig. 3). A needle is attached to the needle adaptor which engages the rubber diaphragm of the dental cartridge (Fig. 4). The anesthetic cartridge is placed into the barrel of the syringe from the side (breech loading).

Figure 3: Breech-loading, metallic, cartridge-type, aspirating syringe

Figure 4: Breech-loading, metallic, cartridge-type, aspirating syringe The barrel contains a piston with a harpoon that engages the rubber stopper at the end of the anesthetic cartridge (Fig. 5, A and B):

Figure 5A: Needle-syringe assembling : The anesthetic cartridge is placed into the barrel of the syringe from the side (breech loading).

Figure 5B: A piston with a harpoon engages the rubber stopper at the end of the anesthetic cartridge while the needle adaptor engages the rubber diaphragm of the dental cartridge After the needle and cartridge have been attached, a brisk tap is given to the back of the thumb ring to ensure the harpoon has engaged the rubber stopper at the end of the anesthetic cartridge (Fig.6, A, B, and C):

Figure 6A

Figure 6B Figure 6A & 6B: Needle-syringe assembling: A brisk tap is given to the back of the thumb ring to ensure the harpoon has engaged the rubber stopper at the end of the anesthetic cartridge.

Figure 6C: A fully loaded anesthetic syringe Dental needles are referred to in terms of their gauge which corresponds to the diameter of the lumen of the needle. Increasing gauge corresponds to smaller lumen diameter. Twenty-five and twenty-seven gauge needles are most commonly used for maxillary and mandibular regional anesthesia and are available in long and short lengths. The length of the needle is measured from the tip of the needle to the hub. The conventional long needle is approximately 40mm in length while the short needle is approximately 25mm in length. Variations in needle length do exist depending upon the manufacturer. Anesthetic cartridges are prefilled, 1.8cc glass cylinders with a rubber stopper at one end and an aluminum cap with a diaphragm at the other end (Fig. 7, A and B). The contents of an anesthetic cartridge are the local anesthetic, vasoconstrictor (anesthetic without vasoconstrictor is also available), preservative for the vasoconstrictor (sodium bisulfite), sodium chloride, and distilled water. The most common anesthetics used in clinical practice are the amide anesthetics lidocaine and mepivacaine. Other amide anesthetics available for use are prilocaine, articaine, bupivacaine, and etidocaine. Esther anesthetics are not as commonly used however remain available. Procaine, procaine plus propoxycaine, chlorprocaine, and tetracaine are some common esther anesthetics.

Figure 7A: Dental cartridges. The rubber stopper is on the right end of the cartridge while the aluminum cap with the diaphragm is on the left end of the cartridge.

Figure 7B: Containers of dental anesthetic Additional armamentarium includes dry gauze, topical antiseptic and anesthetic. The site of injection should be made dry with gauze and a topical antiseptic should be used to clean the area. Topical anesthetic is applied to the area of injection to minimize discomfort during insertion of the needle into the mucous membrane (Fig. 8). Common topical preparations include benzocaine, butacaine sulfate, cocaine hydrochloride, dyclonine hydrochloride, lidocaine, and tetracaine hydrochloride.

Figure 8: Topical anesthesia: Prior to injection, topical anesthetic can be applied on the mucosa in the area of an injection to minimize discomfort to the patient Universal precautions should always be observed by the clinician which include the use of protective gloves, mask and eye protection. After withdrawing the needle once a block has been completed, the needle should always be carefully recapped to avoid accidental needle stick injury to the operator.1 Retraction of the soft tissue for visualization of the injection site should be performed with the use of a dental mirror or retraction instrument. This is recommended for all maxillary and mandibular regional techniques discussed below. Use of an instrument rather than one's fingers will help prevent accidental needle stick injury to the operator. Techniques of Maxillary Regional Anesthesia The techniques most commonly employed in maxillary anesthesia include supraperiosteal (local) infiltration, periodontal ligament (intraligamentary) injection, posterior superior alveolar nerve block, middle superior alveolar nerve block, anterior superior alveolar nerve block, greater palatine nerve block, nasopalatine nerve block, local infiltration of the palate, and intrapulpal injection. Of less clinical application are the maxillary nerve block and intraseptal injection.

Supraperiosteal (Local) Infiltration The supraperiosteal or local infiltration is the one of the simplest and most commonly employed techniques for achieving anesthesia of the maxillary dentition. This technique is indicated when any individual tooth or soft tissue in a localized area is to be treated. Contraindications to this technique are the need to anesthetize multiple teeth adjacent to one another (in which case a nerve block is the preferred technique), acute inflammation and infection in the area to be anesthetized, and less significantly, the density of bone overlying the apices of the teeth. A 25- or 27-gauge short needle is preferred for this technique. Technique- Identify the tooth to be anesthetized and the height of the mucobuccal fold over the tooth. This will be the injection site. The right handed operator should stand at the nine o'clock to ten o'clock position whereas the left handed operator should stand at the two o'clock to three o'clock position. Retract the lip and orient the syringe with the bevel towards bone. This will prevent discomfort from the needle coming into contact with the bone and will minimize the risk of tearing the periosteum with the needle tip. Insert the needle at the height of the mucobuccal fold above the tooth to a depth of no more than a few millimeters and aspirate (Fig 9, A and B). If aspiration is negative, inject one third to one half (0.6-1.2cc) of a cartridge of anesthetic solution slowly, over the course of thirty seconds. Withdraw the syringe and recap the needle. Successful administration will provide anesthesia to the tooth and associated soft tissue within two to four minutes. If adequate anesthesia has not been achieved repeat the procedure and deposit another one third to one half of the cartridge of anesthetic solution.1

Figure 9A: Locate the height of the mucobuccal fold over the tooth to be anesthetized.

Figure 9B: Clinical picture depicting a local infiltration of the maxillary left central incisor tooth. Note the penetration of the needle at the height of the mucobuccal fold above the maxillary left central incisor Periodontal Ligament (Intraligamentary Injection) The periodontal ligament or intraligamentary injection is a useful adjunct to the supraperiosteal injection or a nerve block. Often, it is used to supplement these techniques to achieve profound anesthesia of the area to be treated. Indications for the use of this technique are the need to anesthetize an individual tooth or teeth, need for soft tissue anesthesia in the immediate vicinity of a tooth, and partial anesthesia following a field block or nerve block. A 25- or 27-gauge short needle is preferred for this technique. Technique- Identify the tooth or area of soft tissue to be anesthetized. The sulcus between the gingiva and the tooth is the injection site for the periodontal ligament injection. Position the patient in the supine position. For the right handed operator, retract the lip with a retraction instrument held in the left hand and stand where the tooth and gingiva are clearly visible. The same applies for the left handed operator except that the retraction instrument will be held in the right hand. Hold the syringe parallel to the long axis of the tooth on the mesial or distal aspect. Insert the needle (bevel facing the root), to the depth of the gingival sulcus (Fig. 10). Advance the needle until resistance is met. A small amount of anesthetic (0.2cc) is then administered slowly over the course of twenty to thirty seconds. It is normal to experience resistance to the flow of anesthetic. Successful execution of this technique provides pulpal and soft tissue anesthesia to the individual tooth or teeth to be treated.1

Figure 10: Clinical picture depicting a periodontal ligament injection. Note the position of the needle between the gingival sulcus and tooth with the needle parallel to the long axis of the tooth Posterior Superior Alveolar Nerve Block The posterior superior alveolar (PSA) nerve block, otherwise known as the tuberosity block or the zygomatic block, is used to achieve anesthesia of the maxillary molar teeth up to the 1st molar with the exception of its mesiobuccal root in some cases. One of the potential complications of this technique is the risk of hematoma formation from injection of anesthetic into the pterygoid plexus of veins or accidental puncture of the maxillary artery. Aspiration prior to injection is indicated when the PSA block is given. The indications for this technique are the need to anesthetize multiple molar teeth. Anesthesia can be achieved with fewer needle penetrations providing greater comfort to the patient by preventing the need for multiple injections by the supraperiosteal technique. The PSA can be given to provide anesthesia of the maxillary molars when acute inflammation and infection are present. If inadequate anesthesia is achieved via the supraperiosteal technique, the PSA can be used to achieve more profound anesthesia of a longer duration. The PSA block also provides anesthesia to the premolar region in a certain percentage of cases where the MSA is absent. Contraindications to the procedure are related to the risk of hematoma formation. In individuals with coagulation disorders, care must be taken to avoid injection into the pterygoid plexus or puncture of the maxillary artery. 25- or 27-gauge short needle is preferred for this technique. Technique- Identify the height of the mucobuccal fold over the 2nd molar. This will be the injection site. The right handed operator should stand at the nine o'clock to ten o'clock position whereas the left handed operator should stand at the two o'clock to three o'clock position. Retract the lip with a retraction instrument. Hold the syringe with the bevel toward the bone. Insert the needle at the height of the mucobuccal fold above the maxillary 2nd molar at a 45 degree angle directed superiorly, medially, and posteriorly (one continuous movement). Advance the needle to a depth of three quarters of its total length (Fig. 11, A and B). No resistance should be felt while advancing the needle through the soft tissue. If bone is contacted, the medial angulation is too great. Slowly retract the needle (without removing it) and bring the syringe barrel toward the occlusal plane. This will allow the needle to be angulated slightly more lateral to the posterior aspect of the maxilla. Advance the needle, aspirate, and inject one cartridge of anesthetic solution slowly over the course of one minute aspirating frequently during the administration. Prior to injecting, one should aspirate in two planes to avoid accidental injection into the pterygoid plexus. After the first aspiration, the needle should be rotated one quarter turn. The operator should then reaspirate. If positive aspiration occurs, slowly retract the needle one to two millimeters and reaspirate in two planes. Successful injection technique will result in anesthesia of the maxillary molars (with the exception of the mesiobuccal root of the first molar in some cases), and associated soft tissue on the buccal aspect.1

Figure 11A: Location of the PSA

Figure 11B: Position of the needle during the PSA nerve block. The needle is inserted at the height of the mucobuccal fold above the maxillary 2nd molar at a 45 degree angle aimed superiorly, medially and posteriorly. Middle Superior Alveolar Nerve Block The middle superior alveolar nerve block is useful for procedures where the maxillary premolar teeth or the mesiobuccal root of the 1st molar require anesthesia. Although not always present, it is useful if the posterior or anterior superior alveolar nerve blocks or supraperiosteal infiltration fails to achieve adequate anesthesia. Individuals in whom the MSA nerve is absent, the PSA and ASA nerves provide innervation to the maxillary premolar teeth and the mesiobuccal root of the 1st molar. Contraindications include acute inflammation and infection in the area of injection or a procedure involving one tooth where local infiltration will be sufficient. A 25- or 27-gauge short needle is preferred for this technique. Technique- Identify the height of the mucobuccal fold above the maxillary 2nd premolar. This will be the injection site. The right handed operator should stand at the nine o'clock to ten o'clock position whereas the left handed operator should stand at the two o'clock to three o'clock position. Retract the lip with a retraction instrument and insert the needle until the tip is above the apex of the 2nd premolar tooth (Fig. 12, A and B). Aspirate and inject two thirds to one cartridge of anesthetic solution slowly over the course of one minute. Successful execution of this technique provides anesthesia to the pulp, surrounding soft tissue and bone of the 1st and 2nd premolar teeth and mesiobuccal root of the 1st molar.1

Figure 12A: Location of the MSA nerve.

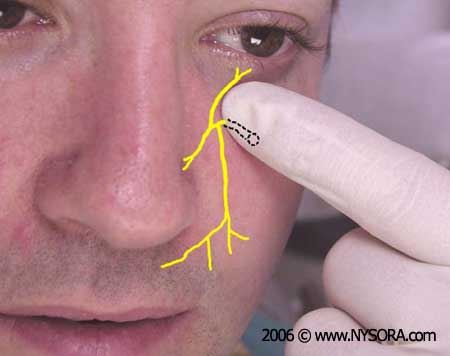

Figure 12B: The needle is inserted at the height of the mucobuccal fold above the maxillary 2nd premolar. Anterior Superior Alveolar Nerve Block/Infraorbital Nerve Block The anterior superior alveolar (ASA) nerve block or infraorbital nerve block is a useful technique for achieving anesthesia of the maxillary central and lateral incisors and canine as well as the surrounding soft tissue on the buccal aspect. In patients that do not have an MSA nerve, the ASA nerve may also innervate the premolar teeth and mesiobuccal root of the 1st molar. Indications for the use of this technique include procedures involving multiple teeth and inadequate anesthesia from the supraperiosteal technique. A 25 gauge long needle is preferred for this technique. Technique- Place the patient in the supine position. Identify the height of the mucobuccal fold above the maxillary 1st premolar. This will be the injection site. The right handed operator should stand at the ten o'clock position whereas the left handed operator should stand at the two o'clock position. Identify the infraorbital notch on the inferior orbital rim (Fig. 13, A). The infraorbital foramen lies just inferior to the notch usually in line with the second premolar. Slight discomfort is felt by the patient when digital pressure is placed on the foramen. It is helpful but not necessary to mark the position of the infraorbital foramen. Retract the lip with a retraction instrument while noting the location of the foramen. Orient the bevel of the needle toward bone and insert the needle at the height of the mucobuccal fold above the 1st premolar (Fig. 13, B). The syringe should be angled toward the infraorbital foramen and kept parallel with the long axis of the 1st premolar to avoid hitting the maxillary bone prematurely. The needle is advanced into the soft tissue until the bone over the roof of the foramen is contacted. This is approximately half the length of the needle however, this will vary from individual to individual. After aspiration, approximately one half to two thirds (0.9-1.2cc) of the anesthetic cartridge is deposited slowly over the course of one minute. It is recommended that pressure be kept over the site of injection to facilitate the diffusion of anesthetic solution into the foramen. Successful execution of this technique results in aesthesia of the lower eyelid, lateral aspect of the nose, and the upper lip. Pulpal anesthesia of the maxillary central and lateral incisors, canine, buccal soft tissue, and bone is also achieved. In a certain percentage of people, the premolar teeth and the mesiobuccal root of the 1st molar is also anesthetized.1

Figure 13A: Location of the infraorbital nerve.

Figure 13B: The needle is kept parallel to the long axis of the maxillary 1st premolar and inserted at the height of the mucobuccal fold above the 1st premolar. Greater Palatine Nerve Block The greater palatine nerve block is useful when treatment is necessary on the palatal aspect of the maxillary premolar and molar dentition. This technique targets the area just anterior to the greater palatine canal. The greater palatine nerve exits the canal and travels forward between the bone and soft tissue of the palate. Contraindications to this technique are acute inflammation and infection at the injection site. A 25- or 27-gauge long needle is preferred for this technique. Technique- The patient should be in the supine position with the chin tilted upward for visibility of the area to be anesthetized. The right handed operator should stand at the eight o'clock position whereas the left handed operator should stand at the four o'clock position. Using a cotton swab, locate the greater palatine foramen by placing it on the palatal tissue approximately one centimeter medial to the junction of the 2nd and 3rd molar (Fig. 14, A and B). While this is the usual position for the foramen, it may be located slightly anterior or posterior to this location. Gently press the swab into the tissue until the depression created by the foramen is felt. Malamed and Trieger found that the foramen is found medial to the anterior half of the 3rd molar approximately 50% of the time, medial to the posterior half of the 2nd molar approximately 39% of the time and medial to the posterior half of the 3rd molar approximately 9% of the time.6 The area approximately one to two millimeters anterior to the foramen is the target injection site. Using the cotton swab, apply pressure to the area of the foramen until the tissue blanches. Aim the syringe perpendicular to the injection site which is one to two millimeters anterior to the foramen. While keeping pressure on the foramen, inject small volumes of anesthetic solution as the needle is advanced through the tissue until bone is contacted. The tissue will blanch in the area surrounding the injection site. Depth of penetration is usually no more than a few millimeters. Once bone is contacted, aspirate and inject approximately one fourth (0.45cc) of anesthetic solution. Resistance to deposition of anesthetic solution is normally felt by the operator. This technique provides anesthesia to the palatal mucosa and hard palate from the 1st premolar anteriorly to the posterior aspect of the hard palate and to the midline medially.1,6

Figure 14A: Location of the greater palatine nerve.

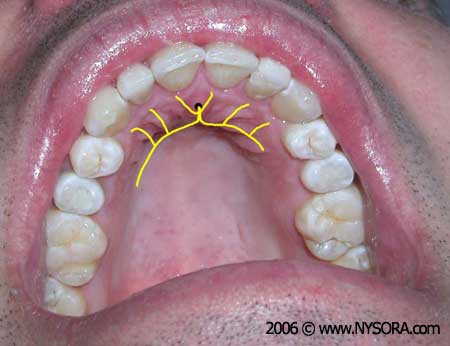

Figure 14B: Area of insertion for the greater palatine nerve block is one centimeter medial to the junction of the maxillary 2nd and 3rd molars. Nasopalatine Nerve Block The nasopalatine nerve block, otherwise known as the incisive nerve block and sphenopalatine nerve block, anesthetizes the nasopalatine nerves bilaterally. In this technique anesthetic solution is deposited in the area of the incisive foramen. This technique is indicated when treatment requires anesthesia of the lingual aspect of multiple anterior teeth. A 25- or 27-gauge short needle is preferred for this technique. Technique- The patient should be in the supine position with the chin tilted upward for visibility of the area to be anesthetized. The right handed operator should be at the nine o'clock position whereas the left handed operator should be at the three o'clock position. Identify the incisive papillae. The area directly lateral to the incisive papilla is the injection site. With a cotton swab, hold pressure over the incisive papilla. Insert the needle just lateral to the papilla with the bevel against the tissue (Fig. 15, A and B). Advance the needle slowly toward the incisive foramen while depositing small volumes of anesthetic and maintaining pressure on the papilla. Once bone is contacted, retract the needle approximately one millimeter, aspirate, and inject one fourth (0.45cc) of a cartridge of anesthetic solution over the course of thirty seconds. Blanching of surrounding tissues and resistance to the deposition of anesthetic solution is normal. Anesthesia will be provided to the soft and hard tissue of the lingual aspect of the anterior teeth from the distal of the canine on one side to the distal of the canine on the opposite side.1

Figure 15A: Location of the nasopalatine nerve.

Figure 15B: Insertion of the needle just lateral to the incisive papilla for the nasopalatine nerve block. Local Palatal Infiltration The administration of local anesthetic for the palatal anesthesia of just one or two teeth is common in clinical practice. When a block is undesirable, local infiltration provides effective palatal anesthesia of the individual teeth to be treated. Contraindications include acute inflammation and infection over the area to be anesthetized. A 25- or 27-gauge short needle is preferred for this technique. Technique- The patient should be in the supine position with the chin tilted upward for visibility of the area to be anesthetized. Identify the area to be anesthetized. The right handed operator should be at the ten o'clock position whereas the left handed operator should be at the two o'clock position. The area of needle penetration is five to ten millimeters palatal to the center of the crown. Apply pressure directly behind the injection site with a cotton swab. Insert the needle at a forty five degree angle to the injection site with the bevel angled toward the soft tissue (Fig. 16). While maintaining pressure behind the injection site, advance the needle and slowly deposit anesthetic solution as the soft tissue is penetrated. Advance the needle until bone is contacted. Depth of penetration is usually no more than a few millimeters. The tissue is very firmly adherent to the underlying periosteum in this region causing resistance to the deposition of local anesthetic. No more than 0.2 to 0.4cc of anesthetic solution is necessary to provide adequate palatal anesthesia. Blanching of the tissue at the injection site immediately follows deposition of local anesthetic. Successful administration of anesthetic using this technique results in hemostasis and anesthesia of the palatal tissue in the area of injection.1

Figure 16: Local infiltration on the palatal aspect of the maxillary right 1st premolar. The needle is inserted approximately 5 to 10mm palatal to the center of the crown. Intrapulpal Injection Intrapulpal injection involves anesthesia of the nerve within the pulp canal of the individual tooth to be treated. When pain control cannot be achieved by any of the aforementioned methods, the intrapulpal method may be used once the pulp chamber is open. There are no contraindications to the use of this technique as it is at times the only effective method of pain control. A 25- or 27-gauge short needle is preferred for this technique. Technique- The patient should be in the supine position with the chin tilted upward for visibility of the area to be anesthetized. Identify the tooth to be anesthetized. The right handed operator should be at the ten o'clock position whereas the left handed operator should be at the two o'clock position. Assuming that the pulp chamber has been opened by an experienced dental professional, place the needle into the pulp chamber and deposit one drop of anesthetic. Advance the needle into the pulp canal and deposit another 0.2cc of local anesthetic solution. It may be necessary to bend the needle in order to gain access to the chamber especially with posterior teeth. The patient usually experiences a brief period of significant pain as the solution enters the canal followed by immediate pain relief.1 |

| 02/20/2016(+ 2016 Dates) | |

| 01/27/2016 | |

| 03/17/2016 | |

| 04/20/2016 | |

| 09/23/2016 | |

| 10/01/2024 |

![[advertisement] gehealthcare](../../../files/banners/banner1_250x600/GEtouch(250X600).gif)

![[advertisement] concertmedical](../../../files/bk-nysora-ad.jpg)

Post your comment