Keys To Success With Peripheral Nerve Blocks

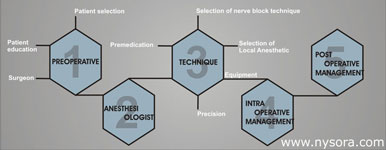

Peripheral nerve block anesthesia offers many clinical advantages that contribute to both an improved patient outcome and lower overall healthcare costs. Peripheral nerve blocks provide excellent anesthesia and postoperative pain relief, fewer side effects than general anesthesia, and facilitate early physical activity. The use of nerve blocks is also associated with reduced use of opioids for postoperative pain, fewer postoperative complications, and earlier discharges. Regional anesthesia is particularly desirable and effective in elderly and high-risk patients undergoing a wide variety of surgical procedures, particularly on the upper and lower extremity. However, the success with peripheral nerve blocks is undoubtedly more anesthesiologist-dependent than is the case with neuraxial and general anesthesia. The main determining factor for success is the anesthesiologist's technical skills and determination, which are required for successful practice of peripheral nerve blocks. To establish a regional anesthesia and peripheral nerve block program, a dedicated team of well-trained anesthesiologists is a prerequisite to assure the consistent peripheral nerve block service. Patient selection To determine if a patient is a candidate for regional anesthesia, factors such as the primary indication for surgery, the presence of coexisting diseases, potential contraindications, and the patient's psychological state should all be considered. Regional anesthesia, alone or in combination with general anesthesia, is feasible and desirable in most surgical patients, in almost any operative site. There are only a few absolute contraindications to regional anesthesia, such as patient refusal, the presence of an active infection at the site of puncture, and, perhaps, true allergy to amide local anesthetics. The contraindications for the use of regional anesthesia are so rare in our practice that we chose to largely omit them in the description of the block techniques. Regional anesthesia is particularly advantageous in high-risk surgical patients undergoing orthopedic, thoracic, abdominal, or vascular surgery. Patients with concomitant respiratory disease also benefit in that the endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation are avoided. Patient education Among the general public, there is a common lack of awareness regarding the potential uses and benefits of regional anesthesia. Patients are commonly offered to choose between two overly simplistic descriptions of anesthesia options: "a needle in the neck" or "go to sleep". However, neither of these accurately describes the nature of the anesthetic care. Many patients, therefore, have a tendency to choose general ("asleep") anesthesia due to the lack of their understanding of what regional anesthesia comprises and the anxiety related to the needle insertion during block performance. In fact, most patients in our practice are appropriately sedated both during block performance and during the actual surgery. Very few of these patients have an unpleasant recollection of their anesthesia experience. Another common misconception is that nerve blocks are associated with an increased risk of nerve injury. In fact, American Society of Anesthesiologists closed-claims studies suggest that the majority of reported neurologic complications are actually associated with general anesthesia because of problems with patient positioning. During the preoperative visit, the anesthesiologist should help the patient understand the basics of the anesthetic management and establish a realistic expectations. Patients should be educated about the principal benefits of regional anesthesia-avoidance of general anesthesia and airway management, improved pain control, and reduced incidence of nausea and vomiting, all of which are evident immediately in the postoperative period. Patients should be instructed on what to expect in the postoperative period. In particular, they should be informed about the duration of the blockade, the need for analgesic therapy as the block is wearing off, and the care of the insensate extremity. Surgeon An insightful, and educated surgeon is often the greatest advocate of regional anesthesia. In our institution, nearly all patients undergoing various orthopedic, vascular, hand, and podiatric surgical procedures are anesthetized using regional anesthesia. While some new surgeons joining the staff have reservations about regional anesthesia, their views are quickly changed once they realize that an increased operating room efficiency and favorable outcomes are associated with expertly performed regional anesthesia procedures. However, the entire department of anesthesiology must be adequately trained in peripheral nerve blocks to provide consistent service and continuity of care. In such an environment, most of our surgeons routinely request regional anesthesia and many patients coming for their procedures already have some basic information and expectations regarding the anesthetic plan. A discussion with the surgeon prior to choosing a regional anesthetic technique is important. The discussion must include considerations regarding the site, nature, extent, and duration of the planned surgical procedure. Discussion of the use of a tourniquet is always necessary to make sure that the intended technique will be adequate for the planned surgery. Anesthesiologist A confident, well trained, and charismatic anesthesiologist is perhaps the single most important factor for the success of regional anesthetic. For patient's acceptance, and successful initiation and conductance of a regional anesthetic, it is primarily the anesthesiologist's confidence and ability to establish a rapport with the patient that determines the success. In our practice, we do not present the patient with a range of anesthetic options for the particular procedure, which many patients find confusing. Instead, we propose to the patient a regional anesthesia plan that is deemed optional based on the patient's physical status, planned procedure, surgical technique, and experience of the anesthesia team. As the number and complexity of regional anesthesia techniques keep increasing, it is clear that regional anesthesia is a highly specialized subspecialty of anesthesiology. A thorough training during residency is necessary to obtain consistent results and avoid complications. A well-structured regional anesthesia fellowship is by far the best path toward success for those who chose to become regional anesthesiologists and acquire the skills necessary to practice the full scope of regional anesthesia and become an effective instructor. Technique Selection Technique selection is of vital importance for the success of nerve block anesthesia. Choosing, initiating, and conducting regional anesthetic often requires more thought process than the conductance of a general anesthetic. With general anesthesia, regardless of the technique, drugs, or ventilation modes chosen, adequate anesthesia is almost assured because all patients are unconscious during the conductance of general anesthetic. In contrast, otherwise successful regional blocks may fail to provide adequate operating conditions because the site and duration of the surgery, the need for tourniquet application, or appropriate perioperative sedation were not considered. General guidelines on selecting nerve block techniques for some specific surgical procedures are provided in the appendix at the end of this chapter. Premedication Most patients are apprehensive about the pending anesthesia and surgery. Therefore, prior to placement of a peripheral nerve block for surgery, premedication is essential to alleviate anxiety and prevent unnecessary discomfort. Inadequately premedicated patients will move during the block placement, making it difficult to interpret responses to nerve stimulation and possibly cause dislodgment of the needle from its intended position. In our practice, we prefer using a combination of benzodiazepine and a short-acting narcotic (alfentanil). It should be noted that different block procedures are associated with varying degrees of discomfort. Premedication is adjusted for individual patients and the procedure. A narcotic analgesic is introduced only at the time of the needle placement. The alfentanil provides intense analgesia of short duration and it is the most commonly used narcotic for this purpose in our practice. All peripheral nerve blocks can be divided into two major groups - blocks associated with minor patient discomfort ("superficial" blocks) and blocks associated with more patient discomfort ("deep" blocks). A sedation protocol should be chosen according to the regional anesthesia technique planned and individual patient characteristics. For instance, interscalene brachial plexus block can be administered to a minimally sedated, fully alert and awake patient. On the other hand, an infraclavicular, sciatic, or lumbar plexus block necessitates, for most patients, a greater degree of sedation and analgesia to ensure the patient's comfort and acceptance. Regardless of the sedation technique chosen, the goal of sedation is to provide maximum patient comfort while maintaining a meaningful patient contact throughout the procedure. In the table below we suggest some premedication protocols. More information on the doses of sedatives and analgesics are suggested in the chapter for each individual block procedure.

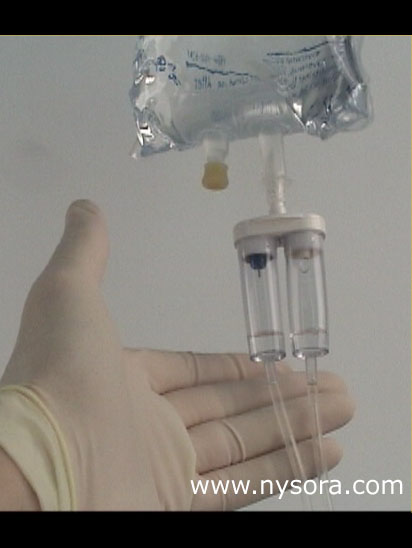

Precision The two main factors for successful neuronal blockade are successful localization of the nerve(s) and the ability to maintain the needle in the same position while the injection of local anesthetic is carried out. Although most trainees learn how to accurately place the needle in the intended position relatively quickly, learning to maintain that position throughout the injection takes more concentrated effort. We teach all our trainees to use a two-hand immobile technique. With this technique, the palpating fingers are firmly pressed in the desired anatomic location while the nonpalpating fingers are anchored on patient's body to prevent moving of the fingers and changing the depth of palpation. The hand holding the needle is then positioned over the palpating hand with free fingers supported on the palpating hand or patient's body. The exact position of the hands during block performance is demonstrated for each individual block technique in their respective chapters. Equipment The proper selection of the equipment, such as needles of the appropriate length and a properly functioning nerve stimulator is very important for successful block performance. Insulated needles are due to their superior stimulating characteristics. It should be noted that there are differences in needle design among various manufacturers, resulting in clinically significant differences in stimulating characteristics, ease of advancement, and internal resistance. Although paresthesia techniques are still taught in some centers, we completely abandoned this practice and teach only the techniques with nerve stimulators. Paresthesia techniques can be used with some upper extremity blocks. However, modern lower extremity and continuous nerve blocks can not be successfully practiced without nerve stimulation. Nerve stimulators also provide useful information on the needle position, allow for an objective and logical needle redirection, and serve as an excellent educational tool for better understanding of the functional anatomy. In our practice, we use nerve stimulators with a remote (foot) control, which allows quick and frequent control of the current by a single anesthesiologist. A remote-controlled nerve stimulator is also ideal in teaching programs because it allows the instructor to control the current while keeping the hands sterile on the patient during resident training. Local Anesthetic Selection Selection of the type, dose, and volume of local anesthetic plays a major role in successful neuronal blockade. Local anesthetics are discussed in detail in each chapter. Adequate volume and concentration are important to ensure fast onset and complete blockade. However, unnecessarily high doses and concentrations should be avoided, particularly in older and ill patients, in whom inadvertent intravascular injection of local anesthetic carries a much higher risk than in the young and fit patient. High pressures and fast forceful injections should be avoided to decrease the risk of massive inadvertent "channeling" of local anesthetic into the systemic circulation. Intraoperative Management Appropriate patient-comfort adjusted sedation is almost always beneficial and adds to the quality level of anesthesia achieved with peripheral nerve blocks. Most surgeons prefer patients to be lightly asleep during surgery to better concentrate on the technical aspects of the operation. Similarly, the majority of patients also prefer not to be "aware" of the activities in the operating room. For outpatients, after completion of the block, sedation is maintained throughout the surgical procedure and adjusted to the patient's comfort. In outpatients, this is most often accomplished using an intravenous infusion of propofol in a dose of 10-30 mcg/kg/min (20-30 mL/hr) while patients are spontaneously breathing. A face mask is routinely applied and oxygen delivered (5-6 l/min). At the completion of the procedure, the infusion is discontinued. After surgery, most patients are fully alert and able to meaningfully discuss the findings with the surgeon in the operating room while the wound dressing is being applied. Upon arrival at the recovery room, most ambulatory surgery patients are fast tracked to the post-anesthesia care unit and prepared for discharge home.  For inpatients, a combination of small boluses of midazolam and propofol are good choices. We avoid the use of narcotics at any point during the intraoperative management of patients receiving regional anesthesia. A small proportion of regional anesthetics will inevitably fail to provide adequate operating conditions due to inadequate anesthesia or difficulties with achieving adequate sedation. When anesthesia is deemed incomplete for the planned surgery, our choice is often to induce a light general anesthetic and control the airway instead of resorting to over-sedation and intravenous narcotics. However, since anesthesia of the skin is often the last to onset, local infiltration by surgeon, when possible, and deeper levels of sedation at the beginning of the procedure are often all that is required for the procedure to proceed while the block is "setting up". Most operating rooms are kept cold and for this reason, all patients undergoing surgery under regional anesthesia should be well warmed by using forced air or warm blankets. Failure to prevent shivering can result in uncontrolled patient's movement, tremors, and a consequent failure of an otherwise successful regional anesthetic. Significant noise levels are often present in operating amphitheatres due to discussion among the staff, handling of instruments, or the use of various pneumatic instruments. In a study on noise levels during various orthopedic surgery procedures, we recorded levels over 100 decibels when pneumatic drills and saws were used. Such noise is invariably noxious to the patient and requires much higher doses of sedatives. Therefore, shielding the patient's ears from the unwanted noise should be done routinely to help reduce the patient's anxiety.  During administration and conductance of regional anesthesia, incremental doses (boluses) of sedatives, narcotics, intravenous sedation, and antibiotics are routinely administered and often there is a tendency to over administer intravenous fluids. Overhydration should be avoided because of the possibility of difficulties intraoperatively when patients need to void. For that reason, it is advisable to use an electronic infusion pump or a micro drip intravenous infusion set. We often use a combination of macro-micro drip IV set (DualFlow) and set the infusion to a slow micro drip rate. Then, we simply open and close the macro drip to quickly flush the injected medications. Such a practice is particularly useful when managing patients with renal failure or a history of congestive heart failure undergoing various procedures under regional anesthesia. The micro drip is used to prevent inadvertent fluid administration but the macro drip is immediately available to allow flushing of the injected medication or resuscitation. Common examples include patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy or arteriovenous graft insertions in the arm under cervical or brachial plexus blocks, respectively. Postoperative Management On completion of the surgical procedure is important to discuss with the surgeons, patient, and nursing staff the expected duration of the motor and sensory blockade to prevent unnecessary concerns by anyone involved in the patient management. In addition, a proper multi modal pain management protocol must be developed and discussed thoroughly with the patient to avoid severe pain when the block(s) wears off. For inpatients, this is perhaps best accomplished by prescribing intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV PCA) or oral analgesics. This applies even for patients who may receive continuous nerve block infusion catheters. For outpatients, such a plan most often consists of a combination of an oral non steroidal anti-inflammatory regimen and an oral acetaminophen-codeine prescription. Clear instructions regarding the care of the insensate extremity should also be given to the patients to prevent secondary injuries, which may occur when the anesthetized extremity is not handled with care. Appendix A confident, well trained, and charismatic anesthesiologist is perhaps the single most important factor for the success of regional anesthetic. For patient's acceptance, and successful initiation and conductance of a regional anesthetic, it is primarily the anesthesiologist's confidence and ability to establish a rapport with the patient that determines the success. In our practice, we do not present the patient with a range of anesthetic options for the particular procedure, which many patients find confusing. Instead, we propose to the patient a regional anesthesia plan that is deemed optional based on the patient's physical status, planned procedure, surgical technique, and experience of the anesthesia team. As the number and complexity of regional anesthesia techniques keep increasing, it is clear that regional anesthesia is a highly specialized subspecialty of anesthesiology. A thorough training during residency is necessary to obtain consistent results and avoid complications. A well-structured regional anesthesia fellowship is by far the best path toward success for those who chose to become regional anesthesiologists and acquire the skills necessary to practice the full scope of regional anesthesia and become an effective instructor.

Bibliography 1. Dickerman D, Vloka JD, Koorn R, Hadzic A: Excessive noise levels during orthopedic surgery. Regional Anesthesia, 1997; 22:97 2. Hadzic A, Vloka JD, Koenigsamen J: Training requirements for peripheral nerve blocks. Current Opinion in Anesthesiology 2002; 15:669-73 3. Hadzic A, Vloka JD, Kuroda MM, et al: The practice of peripheral nerve blocks in the United States: a national survey. Reg Anesth Pain Med 1998; 23:241-6 4. http://www.NYSORA.com, October 18, 2001. 5. Karaca P, Hadzic A, Vloka, JD. Specific Nerve Blocks: An Update. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 2000; 13:549-555. 6. Kopacz D, Neal J, Pollock J: The regional anesthesia "learning curve": What is the minimum number of epidural and spinal blocks to reach consistency? Reg Anesth 1996; 21:182-90 7. Kopacz DJ, Bridenbaugh LD. Are anesthesia residency programs failing regional anesthesia? The past, present, and future. Reg Anesth 1993; 18:84-7. 8. Vloka DJ, Hadzic A. A new intravenous infusion set for use in anesthesia practice. Anesth Analg 1998;86; S207. 9. Vloka, JD, Hadzic A, Santos A. Lower Extremity Nerve Blocks for Ambulatory Surgery. Current Anesthesiology Reports 2000, 2(4):327-332. DISCLAIMER: The material presented on this Web page has not been peer-reviewed. The indications, techniques and dosages on this Web page have been recommended in the medical literature and/or conform to OUR clinical practice. The medications and equipment have not necessarily been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the techniques and dosages for which they are recommended. The package insert for each drug and/or equipment should be consulted for use and dosage as recommended by the FDA. Because standards, practices and recommendations change, it is advisable to keep abreast of revised recommendations, particularly those concerning new drugs and techniques. While the techniques and dosages described are successfully used in our practice, they should be followed with a discretion since their complications may be dependent on the operator, patient and/or other accompanying clinical circumstances. The development and maintenance of this web page has not been supported by any pharmaceutical or medical manufacturing industry. The medications and/or equipment discussed in the web page is shown solely for teaching purposes. Similar equipment or medications from other manufacturers may produce similar clinical results to ours. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![[advertisement] gehealthcare](files/banners/banner1_250x600/GEtouch(250X600).gif)

Post your comment